Boxing (

pugilism,

prize fighting,

the sweet science or in

Greek pygmachia) is a

combat sport in which two people engage in a contest of strength, speed, reflexes, endurance, and will, by throwing

punches with

gloved hands against each other.

Amateur boxing is both an

Olympic and

Commonwealth

sport and is a common fixture in most of the major international

games—it also has its own World Championships. Boxing is supervised by a

referee

over a series of one- to three-minute intervals called rounds. The

result is decided when an opponent is deemed incapable to continue by a

referee, is disqualified for breaking a rule, resigns by

throwing in a towel, or is pronounced the winner or loser based on the judges' scorecards at the end of the contest.

The origin of boxing may be its acceptance by the

ancient Greeks as an

Olympic game

in BCE 688. Boxing evolved from 16th- and 18th-century prizefights,

largely in Great Britain, to the forerunner of modern boxing in the

mid-19th century, again initially in Great Britain and later in the

United States.

Early history

See also Ancient Greek boxing

First depicted in

ancient Egyptian relief from the

2nd millennium BC depicts both fist-fighters and spectators.

[1] Both depictions show bare-fisted contests.

[1] Other depictions in the 2nd millennium BC can be seen in reliefs from the

Mesopotamian nations of

Assyria and

Babylonia, and in

Hittite art from

Asia Minor. The earliest evidence for fist fighting with any kind of gloves can be found on

Minoan Crete (c. 1500–900 BC), and on

Sardinia, if we consider the

boxing statues of Prama mountains (c. 2000–1000 BC).

[1]

Early boxing

Boxing was originally nothing more than bare fist fighting between

two willing and sometimes unwilling competitors. As a sport, fighting

has been around for thousands of years where it first arose in parts of

Africa, including Ancient Egypt before spreading to parts of Southern

Europe. The Ancient Greeks believed that fighting was a game played by

the Gods on Olympus.

The

Romans had a keen interest in the sport and fighting soon became a common spectator

sport. In order for the fighters to protect themselves against their opponents they wrapped

leather thongs around their fists. Eventually harder leather was used and the thong soon became a

weapon. The Romans even introduced metal studs to the thongs to make the

cestus which then led to a more sinister weapon called the myrmex (‘limb piercer’). Fighting events were held at Roman

Amphitheatres.

The Roman form of boxing was often a fight until death to please the

spectators who gathered at such events. However, especially in later

times, purchased slaves and trained combat performers were valuable

commodities, and their lives were not given up without due

consideration. Often slaves were used against one another in a circle

marked on the floor. This is where the term ring came from. In 393

AD, during the Roman

gladiator

period, boxing was abolished due to excessive brutality. It was not

until the late 17th century that boxing re-surfaced in London.

Modern boxing

Broughton's rules (1743)

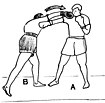

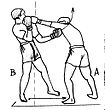

A straight right demonstrated in

Edmund Price's

The Science of Defense: A Treatise on Sparring and Wrestling, 1867

Records of Classical boxing activity disappeared after the fall of the Western

Roman Empire

when the wearing of weapons became common once again and interest in

fighting with the fists waned. However, there are detailed records of

various fist-fighting sports that were maintained in different cities

and provinces of Italy between the 12th and 17th centuries. There was

also a sport in

ancient Rus called

Kulachniy Boy or "Fist Fighting".

As the wearing of swords became less common, there was renewed

interest in fencing with the fists. The sport would later resurface in

England during the early 16th century in the form of

bare-knuckle boxing sometimes referred to as

prizefighting. The first documented account of a bare-knuckle fight in England appeared in 1681 in the

London Protestant Mercury, and the first English bare-knuckle champion was

James Figg in 1719.

[2]

This is also the time when the word "boxing" first came to be used. It

should be noted, that this earliest form of modern boxing was very

different. Contests in Mr. Figg's time, in addition to fist fighting,

also contained fencing and cudgeling. On 6 January 1681, the first

recorded boxing match took place in Britain when

Christopher Monck, 2nd

Duke of Albemarle (and later

Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica) engineered a bout between his butler and his butcher with the latter winning the prize.

Early fighting had no written rules. There were no weight divisions

or round limits, and no referee. In general, it was extremely chaotic.

The first boxing rules, called the Broughton's rules, were introduced by

champion

Jack Broughton in 1743 to protect fighters in the ring where deaths sometimes occurred.

[3]

Under these rules, if a man went down and could not continue after a

count of 30 seconds, the fight was over. Hitting a downed fighter and

grasping below the waist were prohibited. Broughton also invented and

encouraged the use of "mufflers", a form of padded gloves, which were

used in training and exhibitions. The first paper on boxing was

published in the early 1700s by a successful Cornish Wrestler from

Bunnyip, Cornwall, named

Sir Thomas Parkyns, who was also a Physics student of Sir

Isaac Newton.

The paper was actually a single page in his extensive Wrestling &

Fencing manual that entailed a system of headbutting, punching, eye

gouging, chokes, and hard throws not common in modern Boxing.

[4] Parkyns added the techniques described in his paper to his own fighting style.

These rules did allow the fighters an advantage not enjoyed by

today's boxers; they permitted the fighter to drop to one knee to begin a

30-second count at any time. Thus a fighter realizing he was in trouble

had an opportunity to recover. However, this was considered "unmanly"

[5] and was frequently disallowed by additional rules negotiated by the Seconds of the Boxers.

[6]

Intentionally going down in modern boxing will cause the recovering

fighter to lose points in the scoring system. Furthermore, as the

contestants did not have heavy leather gloves and wristwraps to protect

their hands, they used different punching technique to preserve their

hands because the head was a common target to hit full out as almost all

period manuals have powerful straight punches with the whole body

behind them to the face (including forehead) as the basic blows.

[7][8]

London Prize Ring rules (1838)

In

1838, the London Prize Ring rules were codified. Later revised in 1853, they stipulated the following:

[9]

- Fights occurred in a 24 feet (7.3 m)-square ring surrounded by ropes.

- If a fighter were knocked down, he had to rise within 30 seconds under his own power to be allowed to continue.

- Biting, headbutting and hitting below the belt were declared illegal.

Marquess of Queensberry rules (1867)

In 1867, the

Marquess of Queensberry rules were drafted by

John Chambers for amateur championships held at

Lillie Bridge in London for

Lightweights,

Middleweights and

Heavyweights. The rules were published under the patronage of the

Marquess of Queensberry, whose name has always been associated with them.

The June 1894 Leonard–Cushing bout. Each of the six one-minute rounds recorded by the

Kinetograph was made available to exhibitors for $22.50.

[10] Customers who watched the final round saw Leonard score a knockdown.

There were twelve rules in all, and they specified that fights should

be "a fair stand-up boxing match" in a 24-foot-square or similar ring.

Rounds were three minutes with one-minute rest intervals between rounds.

Each fighter was given a ten-second count if he were knocked down, and

wrestling was banned.

The introduction of gloves of "fair-size" also changed the nature of

the bouts. An average pair of boxing gloves resembles a bloated pair of

mittens and are laced up around the wrists.

[11]

The gloves can be used to block an opponent's blows. As a result of

their introduction, bouts became longer and more strategic with greater

importance attached to defensive maneuvers such as slipping, bobbing,

countering and angling. Because less defensive emphasis was placed on

the use of the forearms and more on the gloves, the classical forearms

outwards, torso leaning back stance of the bare knuckle boxer was

modified to a more modern stance in which the torso is tilted forward

and the hands are held closer to the face.

Modern

Through the late nineteenth century, the martial art of boxing or

prizefighting was primarily a sport of dubious legitimacy. Outlawed in

England and much of the United States, prizefights were often held at

gambling venues and broken up by police.

[12]

Brawling and wrestling tactics continued, and riots at prizefights were

common occurrences. Still, throughout this period, there arose some

notable bare knuckle champions who developed fairly sophisticated

fighting tactics.

The English case of

R v. Coney in 1882 found that a

bare-knuckle fight was an

assault occasioning actual bodily harm, despite the

consent of the participants. This marked the end of widespread public bare-knuckle contests in England.

The first world heavyweight champion under the Queensberry Rules was

"Gentleman Jim" Corbett, who defeated

John L. Sullivan in 1892 at the Pelican Athletic Club in

New Orleans.

[13]

Throughout the early twentieth century, boxers struggled to achieve legitimacy, aided by the influence of promoters like

Tex Rickard and the popularity of great champions from John L. Sullivan to

David Olivas.

Rules

The

Marquess of Queensberry rules have been the general rules governing modern boxing since their publication in 1867.

A boxing match typically consists of a determined number of

three-minute rounds, a total of up to 12 rounds (formerly 15). A minute

is typically spent between each round with the fighters in their

assigned corners receiving advice and attention from their coach and

staff. The fight is controlled by a referee who works within the ring to

judge and control the conduct of the fighters, rule on their ability to

fight safely, count knocked-down fighters, and rule on fouls.

Up to three judges are typically present at ringside to score the

bout and assign points to the boxers, based on punches that connect,

defense, knockdowns, and other, more subjective, measures. Because of

the open-ended style of boxing judging, many fights have controversial

results, in which one or both fighters believe they have been "robbed"

or unfairly denied a victory. Each fighter has an assigned corner of the

ring, where his or her coach, as well as one or more "seconds" may

administer to the fighter at the beginning of the fight and between

rounds. Each boxer enters into the ring from their assigned corners at

the beginning of each round and must cease fighting and return to their

corner at the signaled end of each round.

A bout in which the predetermined number of rounds passes is decided

by the judges, and is said to "go the distance". The fighter with the

higher score at the end of the fight is ruled the winner. With three

judges, unanimous and split decisions are possible, as are draws. A

boxer may win the bout before a decision is reached through a

knock-out ; such bouts are said to have ended "inside the distance". If a

fighter is knocked down during the fight, determined by whether the

boxer touches the canvas floor of the ring with any part of their body

other than the feet as a result of the opponent's punch and not a slip,

as determined by the referee, the referee begins counting until the

fighter returns to his or her feet and can continue.

Should the referee count to ten, then the knocked-down boxer is ruled

"knocked out" (whether unconscious or not) and the other boxer is ruled

the winner by

knock-out

(KO). A "technical knock-out" (TKO) is possible as well, and is ruled

by the referee, fight doctor, or a fighter's corner if a fighter is

unable to safely continue to fight, based upon injuries or being judged

unable to effectively defend themselves. Many jurisdictions and

sanctioning agencies also have a "three-knockdown rule", in which three

knockdowns in a given round result in a TKO. A TKO is considered a

knockout in a fighter's record. A "standing eight" count rule may also

be in effect. This gives the referee the right to step in and administer

a count of eight to a fighter that he feels may be in danger, even if

no knockdown has taken place. After counting the referee will observe

the fighter, and decide if he is fit to continue. For scoring purposes, a

standing eight count is treated as a knockdown.

In general, boxers are prohibited from hitting below the belt,

holding, tripping, pushing, biting, or spitting. The boxer's shorts are

raised so the opponent is not allowed to hit to the groin area with

intent to cause pain or injury. Failure to abide by the former may

result in a foul. They also are prohibited from kicking, head-butting,

or hitting with any part of the arm other than the knuckles of a closed

fist (including hitting with the elbow, shoulder or forearm, as well as

with open gloves, the wrist, the inside, back or side of the hand). They

are prohibited as well from hitting the back, back of the neck or head

(called a "rabbit-punch") or the kidneys. They are prohibited from

holding the ropes for support when punching, holding an opponent while

punching, or ducking below the belt of their opponent (dropping below

the waist of your opponent, no matter the distance between).

If a "clinch" – a defensive move in which a boxer wraps his or her

opponents arms and holds on to create a pause – is broken by the

referee, each fighter must take a full step back before punching again

(alternatively, the referee may direct the fighters to "punch out" of

the clinch). When a boxer is knocked down, the other boxer must

immediately cease fighting and move to the furthest neutral corner of

the ring until the referee has either ruled a knockout or called for the

fight to continue.

Violations of these rules may be ruled "fouls" by the referee, who

may issue warnings, deduct points, or disqualify an offending boxer,

causing an automatic loss, depending on the seriousness and

intentionality of the foul. An intentional foul that causes injury that

prevents a fight from continuing usually causes the boxer who committed

it to be disqualified. A fighter who suffers an accidental low-blow may

be given up to five minutes to recover, after which they may be ruled

knocked out if they are unable to continue. Accidental fouls that cause

injury ending a bout may lead to a "no contest" result, or else cause

the fight to go to a decision if enough rounds (typically four or more,

or at least three in a four-round fight) have passed.

Unheard of these days, but common during the early 20th Century in

North America, a "newspaper decision (NWS)" might be made after a no

decision bout had ended. A "no decision" bout occurred when, by law or

by pre-arrangement of the fighters, if both boxers were still standing

at the fight's conclusion and there was no knockout, no official

decision was rendered and neither boxer was declared the winner. But

this did not prevent the pool of ringside newspaper reporters from

declaring a consensus result among themselves and printing a newspaper

decision in their publications. Officially, however, a "no decision"

bout resulted in neither boxer winning or losing. Boxing historians

sometimes use these unofficial newspaper decisions in compiling fight

records for illustrative purposes only. Often, media outlets covering a

match will personally score the match, and post their scores as an

independent sentence in their report.

Professional vs. amateur boxing

Throughout the 17th through 19th centuries, boxing bouts were motivated by money, as the fighters competed for

prize money,

promoters controlled the gate, and spectators bet on the result. The

modern Olympic movement revived interest in amateur sports, and amateur

boxing became an Olympic sport in 1908. In their current form, Olympic

and other amateur bouts are typically limited to three or four rounds,

scoring is computed by points based on the number of clean blows landed,

regardless of impact, and fighters wear protective headgear, reducing

the number of injuries, knockdowns, and knockouts.

[14]

Currently scoring blows in amateur boxing are subjectively counted by

ringside judges, but the Australian Institute for Sport has demonstrated

a prototype of an

Automated Boxing Scoring System,

which introduces scoring objectivity, improves safety, and arguably

makes the sport more interesting to spectators. Professional boxing

remains by far the most popular form of the sport globally, though

amateur boxing is dominant in Cuba and some former Soviet republics. For

most fighters, an amateur career, especially at the Olympics, serves to

develop skills and gain experience in preparation for a professional

career.

Amateur boxing

-

Main article:

Amateur boxing

Amateur boxing may be found at the collegiate level, at the

Olympic Games and

Commonwealth Games,

and in many other venues sanctioned by amateur boxing associations.

Amateur boxing has a point scoring system that measures the number of

clean blows landed rather than physical damage. Bouts consist of three

rounds of three minutes in the Olympic and Commonwealth Games, and three

rounds of three minutes in a national ABA (Amateur Boxing Association)

bout, each with a one-minute interval between rounds.

Competitors wear protective headgear and gloves with a white strip or

circle across the knuckle. A punch is considered a scoring punch only

when the boxers connect with the white portion of the gloves. Each punch

that lands cleanly on the head or torso with sufficient force is

awarded a point. A referee monitors the fight to ensure that competitors

use only legal blows. A belt worn over the torso represents the lower

limit of punches – any boxer repeatedly landing low blows

below the belt

is disqualified. Referees also ensure that the boxers don't use holding

tactics to prevent the opponent from swinging. If this occurs, the

referee separates the opponents and orders them to continue boxing.

Repeated holding can result in a boxer being penalized or ultimately

disqualified. Referees will stop the bout if a boxer is seriously

injured, if one boxer is significantly dominating the other or if the

score is severely imbalanced.

[15]

Amateur bouts which end this way may be noted as "RSC" (referee stopped

contest) with notations for an outclassed opponent (RSCO), outscored

opponent (RSCOS), injury (RSCI) or head injury (RSCH).

Professional boxing

Professional bouts are usually much longer than amateur bouts,

typically ranging from ten to twelve rounds, though four round fights

are common for less experienced fighters or club fighters. There are

also some two-

[16] and three-round professional bouts,

[17]

especially in Australia. Through the early twentieth century, it was

common for fights to have unlimited rounds, ending only when one fighter

quit, benefiting high-energy fighters like

Jack Dempsey.

Fifteen rounds remained the internationally recognized limit for

championship fights for most of the twentieth century until the

early 1980s, when the

death of boxer Duk Koo Kim eventually prompted the

World Boxing Council and other organizations sanctioning professional boxing to reduce the limit to twelve rounds.

Headgear is not permitted in professional bouts, and boxers are

generally allowed to take much more damage before a fight is halted. At

any time, however, the referee may stop the contest if he believes that

one participant cannot defend himself due to injury. In that case, the

other participant is awarded a technical knockout win. A technical

knockout would also be awarded if a fighter lands a punch that opens a

cut on the opponent, and the opponent is later deemed not fit to

continue by a doctor because of the cut. For this reason, fighters often

employ

cutmen,

whose job is to treat cuts between rounds so that the boxer is able to

continue despite the cut. If a boxer simply quits fighting, or if his

corner stops the fight, then the winning boxer is also awarded a

technical knockout victory. In contrast with amateur boxing,

professional male boxers have to be bare chested.

[18]

Boxing styles

Definition of style

"Style" is often defined as the strategic approach a fighter takes

during a bout. No two fighters' styles are alike, as it is determined by

that individual's physical and mental attributes. There are three main

styles in boxing:

out-fighter ("boxer"),

brawler (or "slugger"), and

In-fighter

("swarmer"). These styles may be divided into several special

subgroups, such as counter puncher, etc. The main philosophy of the

styles is, that each style has an advantage over one, but disadvantage

over the other one. It follows the

rock-paper-scissors scenario - boxer beats brawler, swarmer beats boxer, and brawler beats swarmer.

[19]

Boxer/out-fighter

Heavyweight champion

Muhammad Ali is a typical example of an out-fighter.

A classic "boxer" or stylist (also known as an "out-fighter") seeks

to maintain distance between himself and his opponent, fighting with

faster, longer range punches, most notably the jab, and gradually

wearing his opponent down. Due to this reliance on weaker punches,

out-fighters tend to win by point decisions rather than by knockout,

though some out-fighters have notable knockout records. They are often

regarded as the best boxing strategists due to their ability to control

the pace of the fight and lead their opponent, methodically wearing him

down and exhibiting more skill and finesse than a brawler.

[20] Out-fighters need reach, hand speed, reflexes, and footwork.

Notable out-fighters include

Muhammad Ali,

Larry Holmes,

Joe Calzaghe,

Floyd Mayweather Jr.,

Wilfredo Gómez,

Salvador Sanchez,

Cecilia Brækhus,

Gene Tunney,

[21] Ezzard Charles,

[22] Willie Pep,

[23] Meldrick Taylor,

Ricardo Lopez,

Roy Jones, Jr., and

Sugar Ray Leonard. This style was also used by fictional boxer

Apollo Creed.

Boxer-puncher

A boxer-puncher is a well-rounded boxer who is able to fight at close

range with a combination of technique and power, often with the ability

to knock opponents out with a combination and in some instances a

single shot. Their movement and tactics are similar to that of an

out-fighter (although they are generally not as mobile as an

out-fighter),

[24]

but instead of winning by decision, they tend to wear their opponents

down using combinations and then move in to score the knockout. A boxer

must be well rounded to be effective using this style.

Notable boxer-punchers include

Manny Pacquiao,

Wladimir Klitschko,

Lennox Lewis,

Joe Louis,

[25] Wilfredo Gómez,

Oscar de la Hoya,

Archie Moore,

Miguel Cotto,

Nonito Donaire,

Sam Langford,

[26] Henry Armstrong,

[27] Sugar Ray Robinson,

[28] Tony Zale,

Carlos Monzón,

[29] Alexis Argüello,

Erik Morales,

Terry Norris,

Marco Antonio Barrera,

Naseem Hamed,

Thomas Hearns and

Victor Ortiz.

Counter puncher

Counter punchers

are slippery, defensive style fighters who often rely on their

opponent's mistakes in order to gain the advantage, whether it be on the

score cards or more preferably a knockout. They use their well-rounded

defense to avoid or block shots and then immediately catch the opponent

off guard with a well placed and timed punch. A fight with a skilled

counter-puncher can turn into a war of attrition, where each shot landed

is a battle in itself. Thus, fighting against counter punchers requires

constant feinting and the ability to avoid telegraphing ones attacks.

To be truly successful using this style they must have good reflexes, a

high level of prediction and awareness, pinpoint accuracy and speed,

both in striking and in footwork.

Notable counter punchers include

Vitali Klitschko,

Floyd Mayweather, Jr.,

Evander Holyfield,

Max Schmeling,

Chris Byrd,

Jim Corbett,

Jack Johnson,

Bernard Hopkins,

Laszlo Papp,

Jerry Quarry,

Anselmo Moreno,

James Toney,

Marvin Hagler,

Juan Manuel Márquez,

Humberto Soto,

Roger Mayweather,

Pernell Whitaker and

Sergio Gabriel Martinez.

Counter punchers usually wear their opponents down by causing them to

miss their punches. The more the opponent misses, the faster they'll

tire, and the psychological effects of being unable to land a hit will

start to sink in. The counter puncher often tries to outplay their

opponent entirely, not just in a physical sense, but also in a mental

and emotional sense. This style can be incredibly difficult, especially

against seasoned fighters, but winning a fight without getting hit is

often worth the pay-off. They usually try to stay away from the center

of the ring, in order to outmaneuver and chip away at their opponents. A

large advantage in counter-hitting is the forward momentum of the

attacker, which drives them further into your return strike. As such,

knockouts are more common than one would expect from a defensive style.

Brawler/slugger

A brawler is a fighter who generally lacks finesse and footwork in

the ring, but makes up for it through sheer punching power. Mainly

Irish,

Irish-American,

Puerto Rican,

Mexican, and

Mexican-American

boxers popularized this style. Many brawlers tend to lack mobility,

preferring a less mobile, more stable platform and have difficulty

pursuing fighters who are fast on their feet. They may also have a

tendency to ignore combination punching in favour of continuous

beat-downs with one hand and by throwing slower, more powerful single

punches (such as hooks and uppercuts). Their slowness and predictable

punching pattern (single punches with obvious leads) often leaves them

open to counter punches, so successful brawlers must be able to absorb

substantial amounts of punishment. However not all brawler/slugger

fighters are not mobile, some can move around and switch styles if

needed but still have the brawler/slugger style such as

Wilfredo Gómez,

Prince Naseem Hamed and

Danny García.

A brawler's most important assets are power and chin (the ability to

absorb punishment while remaining able to continue boxing). Examples of

this style include

George Foreman,

Danny García,

Wilfredo Gómez,

Sonny Liston,

John L. Sullivan,

Max Baer,

Prince Naseem Hamed,

Ray Mancini,

David Tua,

Arturo Gatti,

Micky Ward,

Michael Katsidis,

James Kirkland,

Marcos Maidana,

Jake Lamotta,

Manny Pacquiao, and Ireland's

John Duddy. This style of boxing was also used by

fictional boxers Rocky Balboa and James "Clubber" Lang.

Brawlers tend to be more predictable and easy to hit but usually fare

well enough against other fighting styles because they train to take

punches very well. They often have a higher chance than other fighting

styles to score a knockout against their opponents because they focus on

landing big, powerful hits, instead of smaller, faster attacks.

Oftentimes they place focus on training on their upper body instead of

their entire body, to increase power and endurance. They also aim to

intimidate their opponents because of their power, stature and ability

to take a punch.

Swarmer/in-fighter

Undefeated heavyweight champion

Rocky Marciano was an excellent swarmer and in-fighter but also had the power of a brawler.

In-fighters/swarmers (sometimes called "pressure fighters") attempt

to stay close to an opponent, throwing intense flurries and combinations

of

hooks and uppercuts. A successful in-fighter often needs a good "

chin" because swarming usually involves being hit with many

jabs

before they can maneuver inside where they are more effective.

In-fighters operate best at close range because they are generally

shorter and have less reach than their opponents and thus are more

effective at a short distance where the longer arms of their opponents

make punching awkward. However, several fighters tall for their division

have been relatively adept at in-fighting as well as out-fighting.

The essence of a swarmer is non-stop aggression. Many short

in-fighters utilize their stature to their advantage, employing a

bob-and-weave defense by bending at the waist to slip underneath or to

the sides of incoming punches. Unlike blocking, causing an opponent to

miss a punch disrupts his balance, permits forward movement past the

opponent's extended arm and keeps the hands free to counter. A distinct

advantage that in-fighters have is when throwing uppercuts where they

can channel their entire bodyweight behind the punch;

Mike Tyson was famous for throwing devastating uppercuts.

Marvin Hagler was known for his hard "

chin",

punching power, body attack and the stalking of his opponents. Some

in-fighters, like Mike Tyson, have been known for being notoriously hard

to hit. The key to a swarmer is aggression, endurance, chin, and

bobbing-and-weaving.

Notable in-fighters include

Julio César Chávez,

Miguel Cotto,

Joe Frazier,

Danny García,

Mike Tyson,

Manny Pacquiao,

Saúl Álvarez,

Rocky Marciano,

Jack Dempsey,

[30] Wayne McCullough,

Harry Greb,

[31][32] David Tua and

Ricky Hatton.

Combinations of styles

All fighters have primary skills with which they feel most

comfortable, but truly elite fighters are often able to incorporate

auxiliary styles when presented with a particular challenge. For

example, an out-fighter will sometimes plant his feet and counter punch,

or a slugger may have the stamina to pressure fight with his power

punches.

Style matchups

There is a generally accepted rule of thumb about the success each of

these boxing styles has against the others. In general, an in-fighter

has an advantage over an out-fighter, an out-fighter has an advantage

over a brawler, and a brawler has an advantage over an in-fighter; these

form a cycle with each style being stronger relative to one, and weaker

relative to another, with none dominating, as in

rock-paper-scissors.

Naturally, many other factors, such as the skill level and training of

the combatants, determine the outcome of a fight, but the widely held

belief in this relationship among the styles is embodied in the cliché

amongst boxing fans and writers that "styles make fights."

Brawlers tend to overcome swarmers or in-fighters because, in trying

to get close to the slugger, the in-fighter will invariably have to walk

straight into the guns of the much harder-hitting brawler, so, unless

the former has a very good chin and the latter's stamina is poor, the

brawler's superior power will carry the day. A famous example of this

type of match-up advantage would be

George Foreman's knockout victory over

Joe Frazier in their original bout "The Sunshine Showdown".

Although in-fighters struggle against heavy sluggers, they typically

enjoy more success against out-fighters or boxers. Out-fighters prefer a

slower fight, with some distance between themselves and the opponent.

The in-fighter tries to close that gap and unleash furious flurries. On

the inside, the out-fighter loses a lot of his combat effectiveness,

because he cannot throw the hard punches. The in-fighter is generally

successful in this case, due to his intensity in advancing on his

opponent and his good agility, which makes him difficult to evade. For

example, the swarming Joe Frazier, though easily dominated by the

slugger George Foreman, was able to create many more problems for the

boxer

Muhammad Ali in their three fights.

Joe Louis, after retirement, admitted that he hated being crowded, and that swarmers like untied/undefeated champ

Rocky Marciano would have caused him style problems even in his prime.

The boxer or out-fighter tends to be most successful against a

brawler, whose slow speed (both hand and foot) and poor technique makes

him an easy target to hit for the faster out-fighter. The out-fighter's

main concern is to stay alert, as the brawler only needs to land one

good punch to finish the fight. If the out-fighter can avoid those power

punches, he can often wear the brawler down with fast jabs, tiring him

out. If he is successful enough, he may even apply extra pressure in the

later rounds in an attempt to achieve a knockout. Most classic boxers,

such as Muhammad Ali, enjoyed their best successes against sluggers.

An example of a style matchup was the historical fight of

Julio César Chávez, a swarmer or in-fighter, against

Meldrick Taylor, the boxer or out-fighter (see

Julio César Chávez vs. Meldrick Taylor).

The match was nicknamed "Thunder Meets Lightning" as an allusion to

punching power of Chávez and blinding speed of Taylor. Chávez was the

epitome of the "Mexican" style of boxing. Taylor's hand and foot speed

and boxing abilities gave him the early advantage, allowing him to begin

building a large lead on points. Chávez remained relentless in his

pursuit of Taylor and due to his greater punching power Chávez slowly

punished Taylor. Coming into the later rounds, Taylor was bleeding from

the mouth, his entire face was swollen, the bones around his eye socket

had been broken, he had swallowed a considerable amount of his own

blood, and as he grew tired, Taylor was increasingly forced into

exchanging blows with Chávez, which only gave Chávez a greater chance to

cause damage. While there was little doubt that Taylor had solidly won

the first three quarters of the fight, the question at hand was whether

he would survive the final quarter. Going into the final round, Taylor

held a secure lead on the scorecards of two of the three judges. Chávez

would have to knock Taylor out to claim a victory, whereas Taylor merely

needed to stay away from the Mexican legend. However, Taylor did not

stay away, but continued to trade blows with Chávez. As he did so,

Taylor showed signs of extreme exhaustion, and every tick of the clock

brought Taylor closer to victory unless Chávez could knock him out. With

about a minute left in the round, Chávez hit Taylor squarely with

several hard punches and stayed on the attack, continuing to hit Taylor

with well-placed shots. Finally, with about 25 seconds to go, Chávez

landed a hard right hand that caused Taylor to stagger forward towards a

corner, forcing Chávez back ahead of him. Suddenly Chávez stepped

around Taylor, positioning him so that Taylor was trapped in the corner,

with no way to escape from Chávez' desperate final flurry. Chávez then

nailed Taylor with a tremendous right hand that dropped the younger man.

By using the ring ropes to pull himself up, Taylor managed to return to

his feet and was given the mandatory 8-count. Referee Richard Steele

asked Taylor twice if he was able to continue fighting, but Taylor

failed to answer. Steele then concluded that Taylor was unfit to

continue and signaled that he was ending the fight, resulting in a TKO

victory for Chávez with only two seconds to go in the bout.

Equipment

Since boxing involves forceful, repetitive punching, precautions must

be taken to prevent damage to bones in the hand. Most trainers do not

allow boxers to train and spar without

wrist wraps and

boxing gloves.

Hand wraps are used to secure the bones in the hand, and the gloves are

used to protect the hands from blunt injury, allowing boxers to throw

punches with more force than if they did not utilize them. Gloves have

been required in competition since the late nineteenth century, though

modern boxing gloves are much heavier than those worn by early

twentieth-century fighters. Prior to a bout, both boxers agree upon the

weight of gloves to be used in the bout, with the understanding that

lighter gloves allow heavy punchers to inflict more damage. The brand of

gloves can also affect the impact of punches, so this too is usually

stipulated before a bout.

A mouth guard is important to protect the teeth and gums from injury,

and to cushion the jaw, resulting in a decreased chance of knockout.

Both fighters must wear soft soled shoes to reduce the damage from

accidental (or intentional) stepping on feet. While older boxing boots

more commonly resembled those of a professional wrestler, modern boxing

shoes and boots tend to be quite similar to their amateur wrestling

counterparts.

Boxers practice their skills on two basic types of punching bags. A

small, tear-drop-shaped "speed bag" is used to hone reflexes and

repetitive punching skills, while a large cylindrical "heavy bag" filled

with sand, a synthetic substitute, or water is used to practice power

punching and body blows. In addition to these distinctive pieces of

equipment, boxers also utilize sport-nonspecific training equipment to

build strength, speed, agility, and stamina. Common training equipment

includes free weights, rowing machines,

jump rope, and

medicine balls.

Boxing matches typically take place in a

boxing ring,

a raised platform surrounded by ropes attached to posts rising in each

corner. The term "ring" has come to be used as a metaphor for many

aspects of prize fighting in general.

Technique

Stance

The modern boxing stance differs substantially from the typical

boxing stances of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The modern stance

has a more upright vertical-armed guard, as opposed to the more

horizontal, knuckles-facing-forward guard adopted by early 20th century

hook users such as

Jack Johnson.

In a fully upright stance, the boxer stands with the legs

shoulder-width apart and the rear foot a half-step in front of the lead

man. Right-handed or orthodox boxers lead with the left foot and fist

(for most penetration power). Both feet are parallel, and the right heel

is off the ground. The lead (left) fist is held vertically about six

inches in front of the face at eye level. The rear (right) fist is held

beside the chin and the elbow tucked against the ribcage to protect the

body. The chin is tucked into the chest to avoid punches to the jaw

which commonly cause knock-outs and is often kept slightly offcenter.

Wrists are slightly bent to avoid damage when punching and the elbows

are kept tucked in to protect the ribcage. Some boxers fight from a

crouch, leaning forward and keeping their feet closer together. The

stance described is considered the "textbook" stance and fighters are

encouraged to change it around once it's been mastered as a base. Case

in point, many fast fighters have their hands down and have almost

exaggerated footwork, while brawlers or bully fighters tend to slowly

stalk their opponents.

Left-handed or southpaw fighters use a mirror image of the orthodox

stance, which can create problems for orthodox fighters unaccustomed to

receiving jabs, hooks, or crosses from the opposite side. The

southpaw stance, conversely, is vulnerable to a straight right hand.

North American fighters tend to favor a more balanced stance, facing

the opponent almost squarely, while many European fighters stand with

their torso turned more to the side. The positioning of the hands may

also vary, as some fighters prefer to have both hands raised in front of

the face, risking exposure to body shots.

Modern boxers can sometimes be seen tapping their cheeks or foreheads

with their fists in order to remind themselves to keep their hands up

(which becomes difficult during long bouts). Boxers are taught to push

off with their feet in order to move effectively. Forward motion

involves lifting the lead leg and pushing with the rear leg. Rearward

motion involves lifting the rear leg and pushing with the lead leg.

During lateral motion the leg in the direction of the movement moves

first while the opposite leg provides the force needed to move the body.

Punches

There are four basic punches in boxing: the jab, cross, hook and

uppercut. Any punch other than a jab is considered a power punch. If a

boxer is right-handed (orthodox), his left hand is the lead hand and his

right hand is the rear hand. For a left-handed boxer or southpaw, the

hand positions are reversed. For clarity, the following discussion will

assume a right-handed boxer.

-

-

Cross - in counter-punch with a looping

-

-

- Jab

– A quick, straight punch thrown with the lead hand from the guard

position. The jab is accompanied by a small, clockwise rotation of the

torso and hips, while the fist rotates 90 degrees, becoming horizontal

upon impact. As the punch reaches full extension, the lead shoulder can

be brought up to guard the chin. The rear hand remains next to the face

to guard the jaw. After making contact with the target, the lead hand is

retracted quickly to resume a guard position in front of the face.

- The jab is recognized as the most important punch in a boxer's

arsenal because it provides a fair amount of its own cover and it leaves

the least amount of space for a counter punch from the opponent. It has

the longest reach of any punch and does not require commitment or large

weight transfers. Due to its relatively weak power, the jab is often

used as a tool to gauge distances, probe an opponent's defenses, harass

an opponent, and set up heavier, more powerful punches. A half-step may

be added, moving the entire body into the punch, for additional power.

Some notable boxers who have been able to develop relative power in

their jabs and use it to punish or 'wear down' their opponents to some

effect include Larry Holmes and Wladimir Klitschko.

- Cross

– A powerful, straight punch thrown with the rear hand. From the guard

position, the rear hand is thrown from the chin, crossing the body and

traveling towards the target in a straight line. The rear shoulder is

thrust forward and finishes just touching the outside of the chin. At

the same time, the lead hand is retracted and tucked against the face to

protect the inside of the chin. For additional power, the torso and

hips are rotated counter-clockwise as the cross is thrown. A measure of

an ideally extended cross is that the shoulder of the striking arm, the

knee of the front leg and the ball of the front foot are on the same

vertical plane.[33]

- Weight is also transferred from the rear foot to the lead foot,

resulting in the rear heel turning outwards as it acts as a fulcrum for

the transfer of weight. Body rotation and the sudden weight transfer is

what gives the cross its power. Like the jab, a half-step forward may be

added. After the cross is thrown, the hand is retracted quickly and the

guard position resumed. It can be used to counter punch a jab, aiming

for the opponent's head (or a counter to a cross aimed at the body) or

to set up a hook. The cross is also called a "straight" or "right",

especially if it does not cross the opponent's outstretched jab.

- Hook

– A semi-circular punch thrown with the lead hand to the side of the

opponent's head. From the guard position, the elbow is drawn back with a

horizontal fist (knuckles pointing forward) and the elbow bent. The

rear hand is tucked firmly against the jaw to protect the chin. The

torso and hips are rotated clockwise, propelling the fist through a

tight, clockwise arc across the front of the body and connecting with

the target.

- At the same time, the lead foot pivots clockwise, turning the left

heel outwards. Upon contact, the hook's circular path ends abruptly and

the lead hand is pulled quickly back into the guard position. A hook may

also target the lower body and this technique is sometimes called the

"rip" to distinguish it from the conventional hook to the head. The hook

may also be thrown with the rear hand. Notable left hookers include Joe Frazier and Mike Tyson.

- Uppercut

– A vertical, rising punch thrown with the rear hand. From the guard

position, the torso shifts slightly to the right, the rear hand drops

below the level of the opponent's chest and the knees are bent slightly.

From this position, the rear hand is thrust upwards in a rising arc

towards the opponent's chin or torso.

- At the same time, the knees push upwards quickly and the torso and

hips rotate anti-clockwise and the rear heel turns outward, mimicking

the body movement of the cross. The strategic utility of the uppercut

depends on its ability to "lift" the opponent's body, setting it

off-balance for successive attacks. The right uppercut followed by a

left hook is a deadly combination employing the uppercut to lift the

opponent's chin into a vulnerable position, then the hook to knock the

opponent out.

These different punch types can be thrown in rapid succession to form

combinations or "combos". The most common is the jab and cross

combination, nicknamed the "one-two combo". This is usually an effective

combination, because the jab blocks the opponent's view of the cross,

making it easier to land cleanly and forcefully.

A large, swinging circular punch starting from a cocked-back position

with the arm at a longer extension than the hook and all of the

fighter's weight behind it is sometimes referred to as a "roundhouse",

"haymaker", or sucker-punch. Relying on body weight and centripetal

force within a wide arc, the roundhouse can be a powerful blow, but it

is often a wild and uncontrolled punch that leaves the fighter

delivering it off balance and with an open guard.

Wide, looping punches have the further disadvantage of taking more

time to deliver, giving the opponent ample warning to react and counter.

For this reason, the haymaker or roundhouse is not a conventional

punch, and is regarded by trainers as a mark of poor technique or

desperation. Sometimes it has been used, because of its immense

potential power, to finish off an already staggering opponent who seems

unable or unlikely to take advantage of the poor position it leaves the

puncher in.

Another unconventional punch is the rarely used

bolo punch,

in which the opponent swings an arm out several times in a wide arc,

usually as a distraction, before delivering with either that or the

other arm.

An illegal punch to the back of the head or neck is known as a

rabbit punch.

Defense

There are several basic maneuvers a boxer can use in order to evade or block punches, depicted and discussed below.

- Slip – Slipping

rotates the body slightly so that an incoming punch passes harmlessly

next to the head. As the opponent's punch arrives, the boxer sharply

rotates the hips and shoulders. This turns the chin sideways and allows

the punch to "slip" past. Muhammad Ali was famous for extremely fast and close slips, as was an early Mike Tyson.

- A slipper will also most likely be a good counter puncher.

Most of the time a slipper will immediately strike their opponent back.

- Sway or fade – To anticipate a punch and move the upper body

or head back so that it misses or has its force appreciably lessened.

Also called "rolling with the punch" or " Riding The Punch".

- Duck or break – To drop down with the back straight so that a punch aimed at the head glances or misses entirely.

- Bob and weave – Bobbing

moves the head laterally and beneath an incoming punch. As the

opponent's punch arrives, the boxer bends the legs quickly and

simultaneously shifts the body either slightly right or left. Once the

punch has been evaded, the boxer "weaves" back to an upright position,

emerging on either the outside or inside of the opponent's

still-extended arm. To move outside the opponent's extended arm is

called "bobbing to the outside". To move inside the opponent's extended

arm is called "bobbing to the inside". Joe Frazier, Jack Dempsey, Mike

Tyson and Rocky Marciano were masters of bobbing and weaving.

- Parry/block – Parrying or blocking

uses the boxer's shoulder, hands or arms as defensive tools to protect

against incoming attacks. A block generally receives a punch while a

parry tends to deflect it. A "palm", "catch", or "cuff" is a defense

which intentionally takes the incoming punch on the palm portion of the

defender's glove. Floyd Mayweather Jr., is a master of this technique.

- The cover-Up – Covering up is the last opportunity (other

than rolling with a punch) to avoid an incoming strike to an unprotected

face or body. Generally speaking, the hands are held high to protect

the head and chin and the forearms are tucked against the torso to

impede body shots. When protecting the body, the boxer rotates the hips

and lets incoming punches "roll" off the guard. To protect the head, the

boxer presses both fists against the front of the face with the

forearms parallel and facing outwards. This type of guard is weak

against attacks from below.

- The clinch – Clinching is a form of trapping or a rough form of grappling

and occurs when the distance between both fighters has closed and

straight punches cannot be employed. In this situation, the boxer

attempts to hold or "tie up" the opponent's hands so he is unable to throw hooks or uppercuts.

To perform a clinch, the boxer loops both hands around the outside of

the opponent's shoulders, scooping back under the forearms to grasp the

opponent's arms tightly against his own body. In this position, the

opponent's arms are pinned and cannot be used to attack. Clinching

is a temporary match state and is quickly dissipated by the referee.

Clinching is technically against the rules, and in amateur fights points

are deducted fairly quickly for it. It is unlikely, however, to see

points deducted for a clinch in professional boxing.

Philly Shell or Shoulder roll defense -This is actually a variation

of the cross-arm defense. The lead arm (left for an orthodox fighter and

right for a southpaw) is placed across the torso usually somewhere in

between the belly button and chest and the lead hand rests on the

opposite side of the fighter's torso. The back hand is placed on the

side of the face (right side for orthodox fighters and left side for

southpaws). The lead shoulder is brought in tight against the side of

the face (left side for orthodox fighters and right side for southpaws).

This style is used by fighters who like to counterpunch.

[35]

To execute this guard a fighter must be very athletic and

experienced. This style is so effective for counterpunching because it

allows fighters to slip punches by rotating and dipping their upper body

and causing blows to glance off the fighter. After the punch glances

off, the fighter's back hand is in perfect position to hit their

out-of-position opponent. The shoulder lean is used in this stance. To

execute the shoulder lean a fighter rotates and ducks (to the right for

orthodox fighters and to the left for southpaws) when their opponents

punch is coming towards them and then rotates back towards their

opponent while their opponent is bringing their hand back.

The fighter will throw a punch with their back hand as they are

rotating towards their undefended opponent. The weakness to this style

is that when a fighter is stationary and not rotating they are open to

be hit so a fighter must be athletic and well conditioned to effectively

execute this style. To beat this style, fighters like to jab their

opponents shoulder causing the shoulder and arm to be in pain and to

demobilize that arm. Fighters that used this defense include Sugar Ray

Robinson, Ken Norton (also used this defense), Pernell Whitaker, James

Toney, and Floyd Mayweather Jr.. Floyd Mayweather Jr., is considered to

be the master of this technique.

Less common strategies

- The "rope-a-dope" strategy : Used by Muhammad Ali in his 1974 "the Rumble in the Jungle"

bout against George Foreman, the rope-a-dope method involves lying back

against the ropes, covering up defensively as much as possible and

allowing the opponent to attempt numerous punches. The back-leaning

posture, which does not cause the defending boxer to become as

unbalanced as they would during normal backward movement, also maximizes

the distance of the defender's head from his opponent, increasing the

probability that punches will miss their intended target. Weathering the

blows that do land, the defender lures the opponent into expending

energy while conserving his/her own. If successful, the attacking

opponent will eventually tire, creating defensive flaws which the boxer

can exploit. In modern boxing, the rope-a-dope is generally discouraged

since most opponents are not fooled by it and few boxers possess the

physical toughness to withstand a prolonged, unanswered assault.

Recently, however, eight-division world champion Manny Pacquiao skillfully used the strategy to gauge the power of welterweight titlist Miguel Cotto in November 2009. Pacquiao followed up the rope-a-dope gambit with a withering knockdown.

- Bolo punch : Occasionally seen in Olympic boxing, the bolo is an arm punch which owes its power to the shortening of a circular arc

rather than to transference of body weight; it tends to have more of an

effect due to the surprise of the odd angle it lands at rather than the

actual power of the punch. This is more of a gimmick than a technical

maneuver; this punch is not taught, being on the same plane in boxing

technicality as is the Ali shuffle. Nevertheless, a few professional boxers have used the bolo-punch to great effect, including former welterweight champions Sugar Ray Leonard, and Kid Gavilan. Middleweight champion Ceferino Garcia is regarded as the inventor of the bolo punch.

- Overhand right :

The overhand right is a punch not found in every boxer's arsenal.

Unlike the right cross, which has a trajectory parallel to the ground,

the overhand right has a looping circular arc as it is thrown

over-the-shoulder with the palm facing away from the boxer. It is

especially popular with smaller stature boxers trying to reach taller

opponents. Boxers who have used this punch consistently and effectively

include former heavyweight champions Rocky Marciano and Tim Witherspoon, as well as MMA champions Chuck Liddell and Fedor Emelianenko. The overhand right has become a popular weapon in other tournaments that involve fist striking.

- Check hook :

A check hook is employed to prevent aggressive boxers from lunging in.

There are two parts to the check hook. The first part consists of a

regular hook. The second, trickier part involves the footwork. As the

opponent lunges in, the boxer should throw the hook and pivot on his

left foot and swing his right foot 180 degrees around. If executed

correctly, the aggressive boxer will lunge in and sail harmlessly past

his opponent like a bull missing a matador. This is rarely seen in

professional boxing as it requires a great disparity in skill level to

execute. Technically speaking it has been said that there is no such

thing as a check hook and that it is simply a hook applied to an

opponent that has lurched forward and past his opponent who simply hooks

him on the way past. Others have argued that the check hook exists but

is an illegal punch due to it being a pivot punch which is illegal in

the sport.

Floyd Mayweather, Jr. employed the use of a check hook against

Ricky Hatton,

which sent Hatton flying head first into the corner post and being

knocked down. Hatton managed to get himself to his feet after the

knockdown but was clearly dazed and it was only a matter of moments

before Mayweather landed a flurry of punches which sent Hatton crashing

to the canvas, giving Mayweather a TKO victory in the 10th round and

handing Hatton his first defeat.

Ring corner

Boxer Yusuf Ahmed in corner of the ring.

In boxing, each fighter is given a corner of the ring where he rests

in between rounds and where his trainers stand. Typically, three men

stand in the corner besides the boxer himself; these are the trainer,

the assistant trainer and the

cutman.

The trainer and assistant typically give advice to the boxer on what he

is doing wrong as well as encouraging him if he is losing. The cutman

is a cutaneous

doctor

responsible for keeping the boxer's face and eyes free of cuts and

blood. This is of particular importance because many fights are stopped

because of cuts that threaten the boxer's eyes.

In addition, the corner is responsible for stopping the fight if they

feel their fighter is in grave danger of permanent injury. The corner

will occasionally throw in a white towel to signify a boxer's surrender

(the idiomatic phrase "to throw in the towel", meaning to give up,

derives from this practice).

[36] This can be seen in the fight between

Diego Corrales and

Floyd Mayweather. In that fight, Corrales' corner surrendered despite Corrales' steadfast refusal.

Medical concerns

Knocking a person unconscious or even causing

concussion may cause permanent

brain damage.

[37] There is no clear division between the force required to knock a person out and the force likely to kill a person.

[38] Since 1980, more than 200 amateur boxers, professional boxers and

Toughman fighters have died due to ring or training injuries.

[39] In 1983, the

Journal of the American Medical Association

called for a ban on boxing. The editor, Dr. George Lundberg, called

boxing an "obscenity" that "should not be sanctioned by any civilized

society."

[40] Since then, the British,

[41] Canadian

[42] and Australian

[43] Medical Associations also have called for bans on boxing.

Supporters of the ban state that boxing is the only sport where

hurting the other athlete is the goal. Dr. Bill O'Neill, boxing

spokesman for the

British Medical Association,

has supported the BMA's proposed ban on boxing: "It is the only sport

where the intention is to inflict serious injury on your opponent, and

we feel that we must have a total ban on boxing."

[44]

Opponents respond that such a position is misguided opinion, stating

that amateur boxing is scored solely according to total connecting blows

with no award for "injury". They observe that many skilled professional

boxers have had rewarding careers without inflicting injury on

opponents by accumulating scoring blows and avoiding punches winning

rounds scored 10-9 by the

10-point must system, and they note that there are many other sports where concussions are much more prevalent.

[45] In 2007, one study of amateur boxers showed that protective headgear did not prevent brain damage,

[46] and another found that amateur boxers faced a high risk of brain damage.

[47]

The Gothenburg study analyzed temporary levels of neurofiliment light

in cerebral spinal fluid which they conclude is evidence of damage, even

though the levels soon subside. More comprehensive studies of

neurologiocal function on larger samples performed by Johns Hopkins

University and accident rates analyzed by National Safety Council show

amateur boxing is a comparatively safe sport.

In 1997, the American Association of Professional Ringside Physicians

was established to create medical protocols through research and

education to prevent injuries in boxing.

[48][49]

Professional boxing is forbidden in

Norway,

Iceland,

Iran and

North Korea. It was banned in

Sweden until 2007

[50] when the ban was lifted but strict restrictions, including four three-minute rounds for fights, were imposed.

[citation needed] It was banned in Albania from 1965 till the fall of Communism in 1991; it is now legal.

Boxing Hall of Fame

Stamp honoring undefeated heavyweight champion

Gene Tunney

The sport of boxing has two internationally recognized boxing halls of fame; the

International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF) and the

World Boxing Hall of Fame (WBHF), with the IBHOF being the more widely recognized boxing hall of fame.

The WBHF was founded by Everett L. Sanders in 1980. Since its

inception the WBHOF has never had a permanent location or museum, which

has allowed the more recent IBHOF to garner more publicity and prestige.

Among the notable names

[citation needed] in the WBHF are

Ricardo "Finito" Lopez,

Gabriel "Flash" Elorde,

Michael Carbajal,

Khaosai Galaxy,

Henry Armstrong,

Jack Johnson,

Roberto Durán,

George Foreman,

Ceferino Garcia and

Salvador Sanchez. Boxing's International Hall of Fame was inspired by a tribute an American town held for two local heroes in 1982. The town,

Canastota, New York, (which is about 15 miles (24 km) east of Syracuse, via the New York State Thruway), honored former world

welterweight/

middleweight champion

Carmen Basilio and his nephew, former world welterweight champion

Billy Backus.

The people of Canastota raised money for the tribute which inspired the

idea of creating an official, annual hall of fame for notable boxers.

The

International Boxing Hall of Fame opened in Canastota in 1989. The first inductees in 1990 included Jack Johnson,

Benny Leonard, Jack Dempsey, Henry Armstrong,

Sugar Ray Robinson,

Archie Moore, and Muhammad Ali. Other world-class figures

[citation needed] include Salvador Sanchez, Fabio Martella, Roberto "Manos de Piedra" Durán,

Ricardo Lopez,

Gabriel "Flash" Elorde,

Vicente Saldivar, Ismael Laguna, Eusebio Pedroza, Carlos Monzón, Azumah Nelson,

Rocky Marciano, Pipino Cuevas and

Ken Buchanan. The Hall of Fame's induction ceremony is held every June as part of a four-day event.

The fans who come to Canastota for the Induction Weekend are treated

to a number of events, including scheduled autograph sessions, boxing

exhibitions, a parade featuring past and present inductees, and the

induction ceremony itself.

Governing and sanctioning bodies

- Governing Bodies

- Sanctioning Bodies

- Amateur